Pakistan’s VPN Conundrum Could Slow Its Digital Economy

- Global Growth: VPN market booming worldwide, projected to hit $90 billion by 2027.

- Local Regulation: Pakistan’s VPN licensing limits freelancers, raising privacy and enforcement concerns.

- Economic Impact: Restrictions may hurt Pakistan’s competitiveness against India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines.

The global Virtual Private Network (VPN) market has seen rapid growth in recent years, evolving from a niche corporate security tool into a mainstream consumer product. As of 2024, the global VPN industry was valued between $44 billion and $50 billion, and is projected to reach $75–90 billion by 2027.

This surge is mainly driven by rising concerns over online privacy, cyber threats, and the global shift to remote and hybrid work. A VPN allows users to appear as if they are connecting from another country or a secure office location, helping protect sensitive data and access region-restricted services.

Apart from professional use, consumer demand has also grown as users increasingly turn to VPNs to bypass geo-blocked content on streaming platforms.

Pakistan’s VPN Conundrum

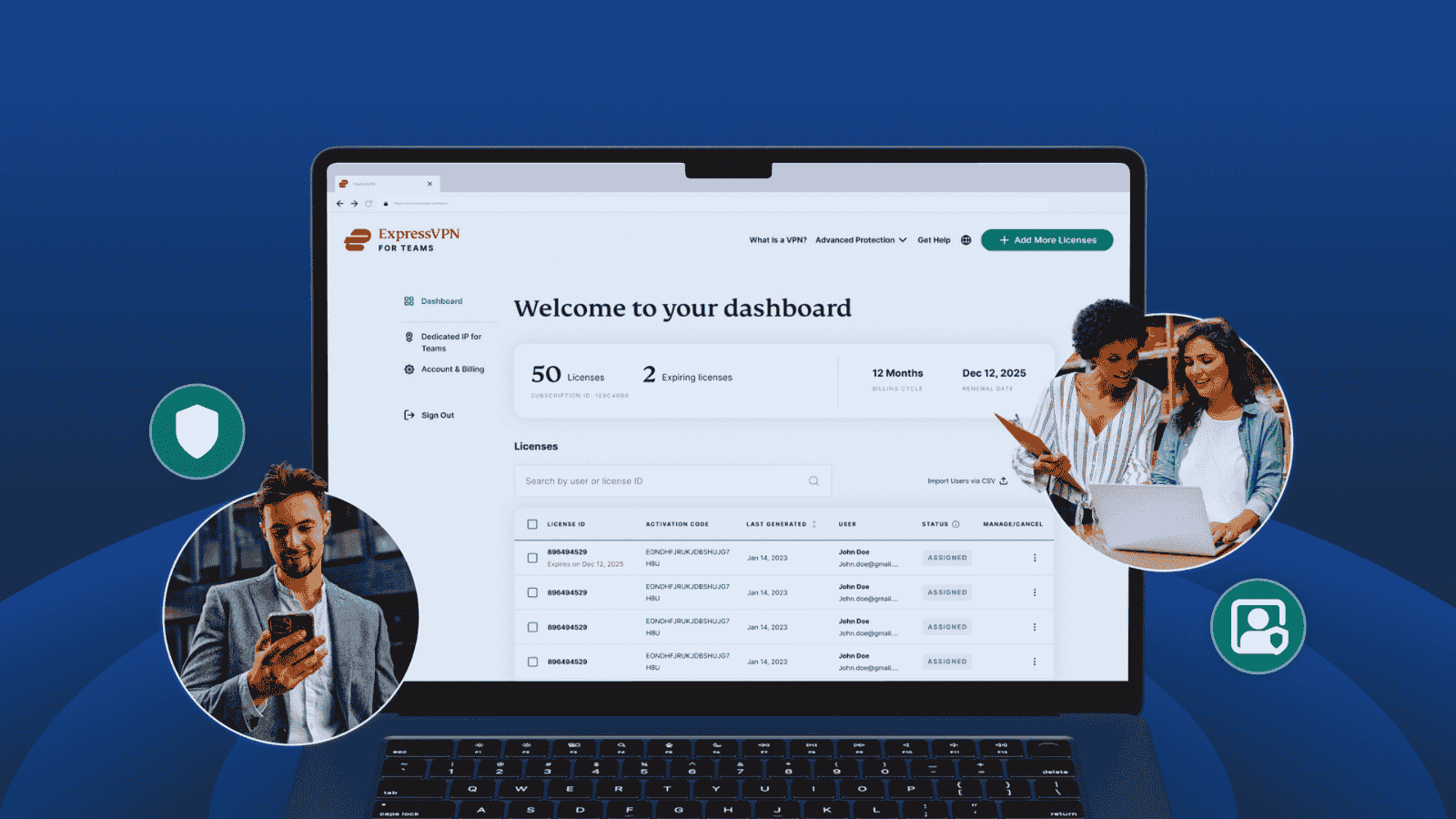

In Pakistan, however, regulatory changes may be affecting this growing digital ecosystem. The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) introduced a VPN Conundrum - VPN registration framework to monitor and manage VPN use across the country.

As of July 2025, the PTA had registered eight VPN service providers, of which only four, PTCL, National Telecommunication Corporation (NTC), Alpha 3 Cubic (Steer Lucid), and Zettabyte (Crest VPN) have been granted operational approval.

This marks slight progress from April 2025, when only three licences had been issued. However, most VPN services used by Pakistani freelancers remain outside the official framework, leaving them in a regulatory grey zone.

The registration process requires static IP addresses, and while there is no fee for basic registration, a nominal charge applies for whitelisting five or more IPs. The PTA has directed banks, IT firms, embassies, and freelancers to register their VPNs, acknowledging their legitimate operational needs.

Privacy and Enforcement Concerns

Despite these measures, privacy advocates and industry experts have raised concerns. Many fear that licensing requirements could force VPN providers to log and share user data with authorities, contradicting the no-log policies central to most commercial VPN services.

While the complete terms of Pakistan’s Class Licence for Data Services have not been publicly disclosed, the PTA’s oversight powers are seen by global providers as incompatible with their privacy commitments.

Enforcement also remains a technical challenge. Detecting VPN traffic requires deep packet inspection (DPI), a method VPN protocols are constantly evolving to evade. As a result, implementation may be uneven: large organizations can comply with regulations more easily, while individual freelancers and startups face significant barriers.

The attempt to distinguish between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” VPN use may also prove unworkable. Freelancers and developers often rely on multiple international platforms, from GitHub to payment gateways, some of which face intermittent restrictions in Pakistan.

Adding to the challenge, the PTA currently lacks a dedicated laboratory to audit the wide variety of VPN tools available. Historically, VPN misuse has raised concerns globally; for instance, Facebook’s Onavo Protect was used to collect data on competitors, while fake VPNs have been deployed by state actors for cyber espionage.

A Strategic Crossroad for Pakistan’s Digital Future

Experts suggest that Pakistan could benefit from recognizing VPNs as part of critical digital infrastructure rather than a threat by default. Instead of restrictions, the PTA could issue usage advisories and invest in domestic digital infrastructure, improving bandwidth, reducing latency, and ensuring reliable access to online platforms.

Pakistan competes with India, Bangladesh, and the Philippines in IT and digital services, all of which maintain more open internet environments. Every regulatory hurdle or service disruption in Pakistan risks shifting the competitive edge toward these rivals.

With thousands of VPN providers globally and hundreds of thousands of Pakistani users depending on VPNs for legitimate work, the PTA faces a complex challenge: building a policy that balances national security, data privacy, and economic competitiveness.