UK Children’s Commissioner Calls for VPN Age Checks to Close Online Safety Loophole

- UK Commissioner’s Call: Dame Rachel de Souza urges VPN providers to add strong age verification safeguards.

- Survey Findings: Most under-18s still access porn despite new Online Safety Act restrictions.

- Industry Concerns: Experts warn VPN curbs could harm privacy, cybersecurity, schools, and legitimate use.

England’s Children’s Commissioner has urged the UK government to tackle what she sees as a major flaw in its new Online Safety Act: young people bypassing age checks using VPNs.

In a new report published today, Dame Rachel de Souza said the government should require VPN providers to implement “highly effective age assurance” to stop under-18s from dodging restrictions. She warned that without action, the law’s protections could be undermined.

The Online Safety Act and Its Challenges

The Online Safety Act, which came into force in July, requires commercial pornography sites to verify that users are over 18. Websites failing to comply face fines of up to £18 million or 10 percent of their global revenue.

Since July 25, Ofcom has launched investigations into 34 major adult platforms serving UK users. Early indicators suggest the new rules are working: data from Similarweb shows Pornhub traffic in the UK dropped by 47 percent, from 3.2 million visits in July to 2 million during the first nine days of August.

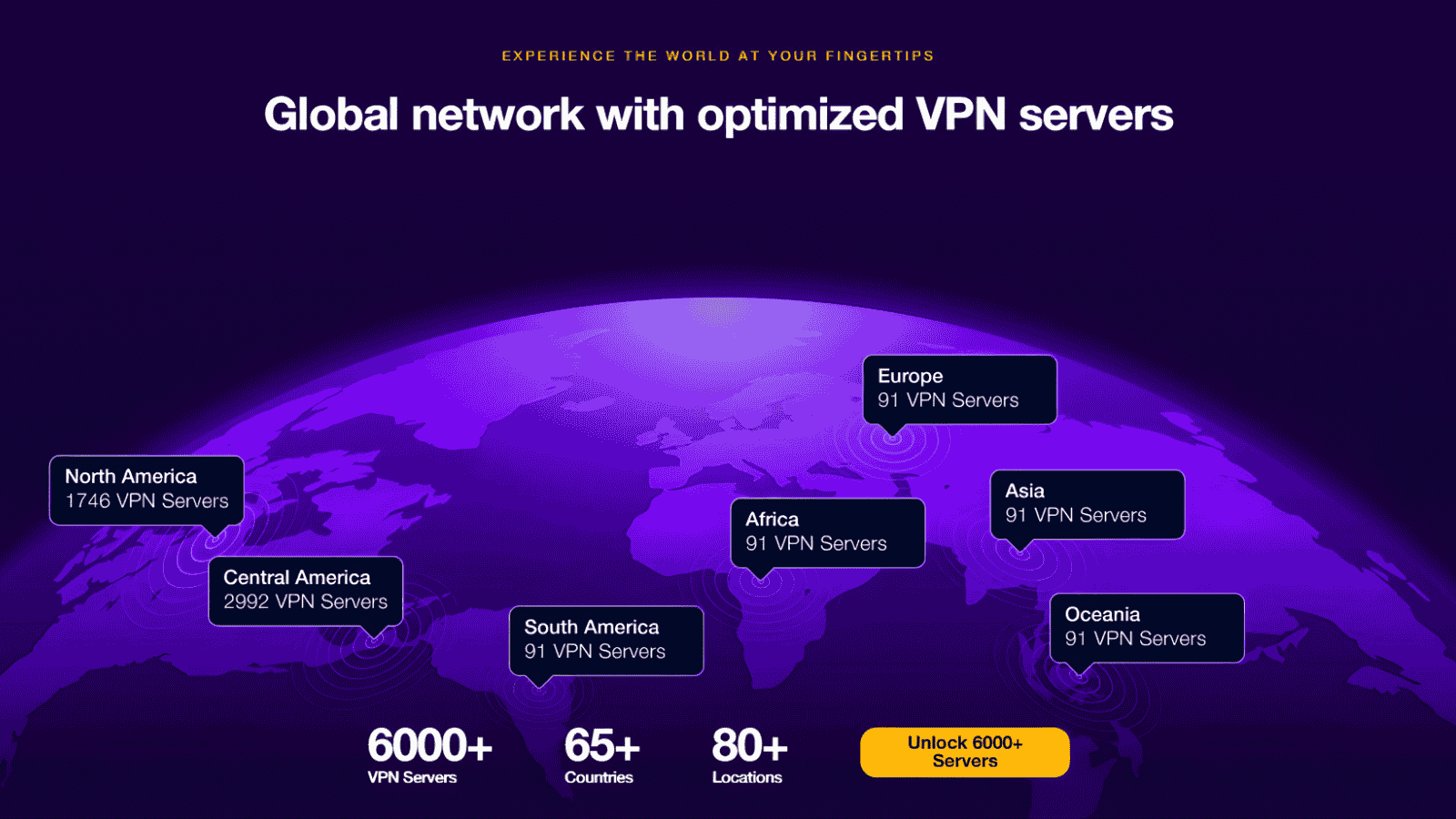

But while the crackdown reduced direct traffic, it has also fueled VPN adoption. These tools let users disguise their location and sidestep website restrictions, leaving regulators with a new problem.

UK Commissioner on VPN: Survey Findings Raise Concerns

The commissioner’s office surveyed 16- to 21-year-olds and found troubling results for policymakers. More respondents reported exposure to pornography before turning 18 than in 2023. Over a quarter said they first encountered porn by age 11, and seven in ten had seen it before adulthood.

De Souza’s report argues that without restrictions on VPNs, underage access to pornography will continue. She suggested amending the Online Safety Act so that UK VPN providers are required to screen underage users and block them from visiting pornographic sites.

Industry Warnings and Wider Risks

Privacy and cybersecurity experts have pushed back against the idea, saying VPN restrictions could harm legitimate users. “The only way to do it is badly,” Graeme Stewart, public sector head at Check Point Software, told The Register last month.

He noted that restricting VPNs would effectively force internet providers to block encrypted traffic, undermining privacy, cybersecurity, and even business operations. Some schools also rely on VPNs to give students secure access to exam boards, research databases, and internal systems, uses that have nothing to do with bypassing content filters.

Government Response

The government has defended its position on online safety, stressing that children’s protection remains the top priority.

“Children have been left to grow up in a lawless online world for too long, bombarded with pornography and harmful content that can scar them for life,” a spokesperson told The Register. “The Online Safety Act is changing that. VPNs are legal tools for adults and there are no plans to ban them. But if platforms deliberately push workarounds like VPNs to children, they face tough enforcement and heavy fines.”

The Online Safety Act has already faced years of delays and criticism from tech companies and civil liberties groups. Bringing VPN providers into the fold would add another layer to an already heated debate over online freedoms and child protection in the UK.